Why Outer Space Needs Anthropologists (and Vice Versa)

SHARE THIS

SHARE THIS

OUTER SPACE NEEDS ANTHROPOLOGISTS

Martin Heidegger was horrified when he saw the first images of the Earth taken from outer space. For this German philosopher, leaving the planet implied a profound uprooting of humanity from its home. But Hans Blumenberg, Heidegger’s contemporary, had a more nuanced reaction. In the wake of the Apollo missions, Blumenberg called for the creation of a discipline he termed “astronoetics”, a humanist substitute for astronauts which would attempt to find a balance between “centrifugal curiosity” and “centripetal care”. This combination of looking up and looking down resonates for me, an anthropologist studying outer space imaginaries. Like astronoetics, my discipline revolves around care and curiosity, along with a healthy dose of criticism. But unlike Blumenberg’s own discipline of philosophy, anthropology tends toward the empirical, as its practitioners produce knowledge through interactions with social actors in particular situations.

How, then, you might ask, can this most human and Earth-centered of disciplines contribute to the study of outer space? Space is cold, dark, and inhospitable to humans. And not only that, anthropology’s central methodology, ethnography, has long relied on a “being there” that can hardly apply to extraterrestrial contexts. The recent boom in anthropological studies of outer space, however, provokes us to think in a new way, both about anthropology and about outer space. Anthropology and outer space studies share some common concerns.

What do humans have in common and what makes us different? How do human groups define themselves with relation to “others”? How do we adapt to particular conditions and situations? How do we think about our pasts? How do we imagine our futures? How do social, political, economic, and technological structures limit or empower us? How are these structures justified and, at least sometimes, resisted? All these questions, I argue, can, and in many cases have been, applied to the study of outer space. An anthropological approach to outer space becomes more logical if we recognize that, in general, outer space imaginaries are created on Earth, both constrained and made possible by earthly social, political, economic, and ecological conditions and created within cultural, historical and geographical contexts. Therefore, much outer space anthropology has focused on the view from below.

COSMIC HUMANITY

Certainly, only a few humans—less than 600 at this writing— have ever actually been in outer space, if we define it physically in terms of the Kármán line, located at 100 kilometers above the surface of the Earth. But if we define space in other than physical terms, humans have always been there. Anthropologist Jane Young, for example, cites a colleague who had worked in Alaska with Inuit peoples. The colleague spoke with her native interlocutors of the Apollo Moon landings, to which the Inuits replied, laughing, “We didn’t know this was the first time you white people had been to the moon. Our shamans have been going for years. They go all the time.” From longstanding anthropological work on archaeo- and ethno-astronomy to more novel topics, such as Debbora Battaglia edited book on “E. T. cultures” and technospirituality, Deanna Weibel’s study of space exploration as pilgrimage, Lytkin Vladimirovich’s work on Russian cosmism, and Susan Lepselter’s ruminations on the poetics of UFO conspiracy theories and alien abduction, humanity’s cosmic leanings have always been fair game for anthropological study, as they point to questions of identity and alterity, as well as humanity’s need to transcend mundane existence.

SPACE ARTIFACTS

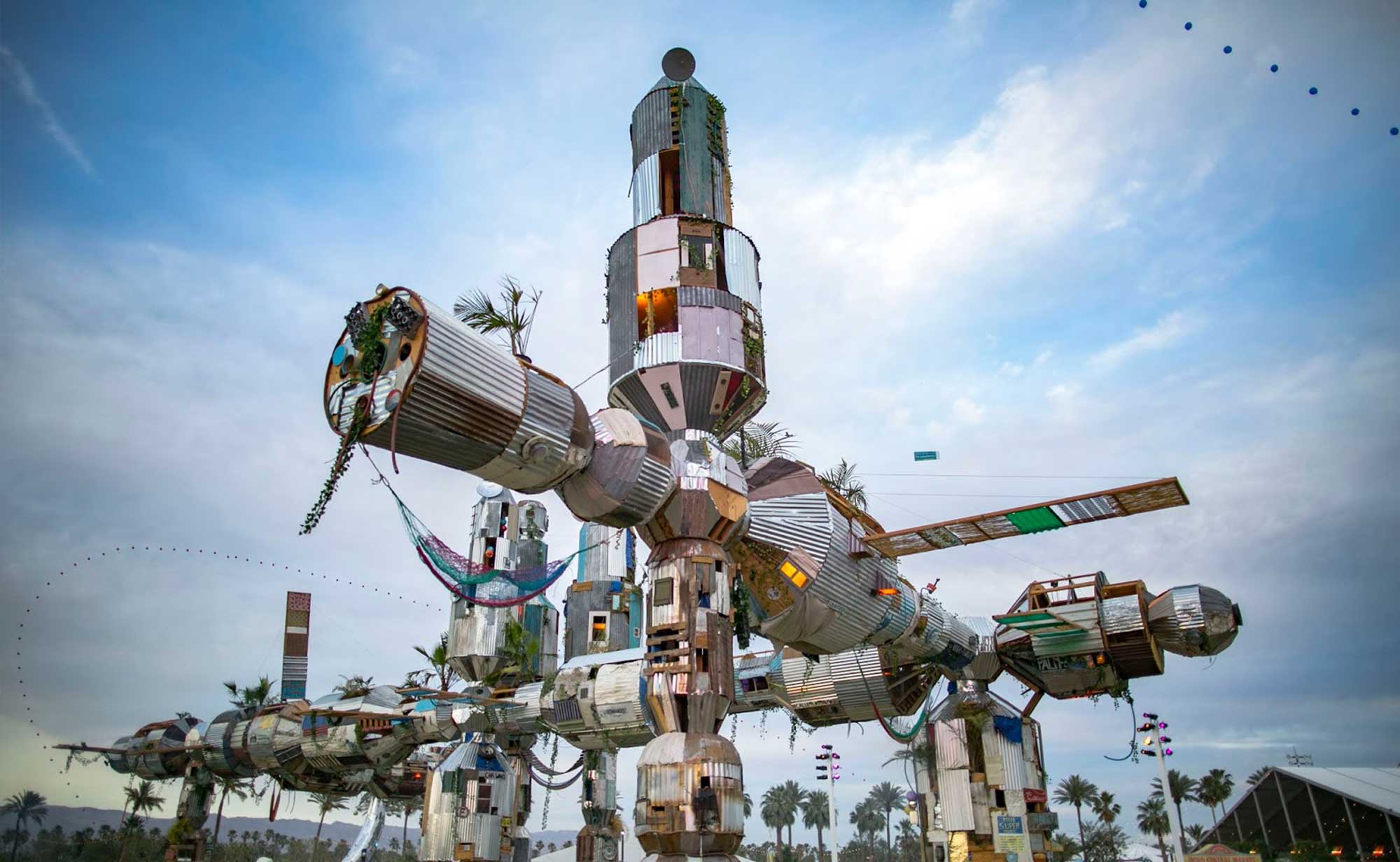

On the other hand, if it’s true that there haven’t been many human bodies in space, human artifacts abound, evidenced by satellites, rovers and robots, probes, an ever-increasing amount of “space junk,” and even sports cars. From a material culture perspective, then, works such as Janet Vertesi’s book on NASA’s Mars Exploration Rover Mission, encourages us to “see like a rover.” Joshua Barker narrates the history of Indonesia’s satellite system and its importance for the creation of a national imaginary of “progress.” And archaeologist and heritage expert Alice Gorman writes of the significance of human artefacts outside the Earth: culturally meaningful objects such as the objects left on the Moon as part of the Apollo program, as well as the thousands and thousands of bits of debris orbiting our planet.

Gorman and other archaeologists also write about the importance of the material remains of space activities on Earth itself, especially

those sites now littered abandoned bits of space technology, the ruins of once-promising futurist projects.

SCIENCE AND TECHNOLOGY

The science, technology and administration of space exploration have also been objects of the anthropological gaze. Lisa Messeri, for example, writes of how scientists in the United States turn “space” into “place” through a series of discursive and embodied practices, like naming, mapping, and undergoing analog missions. Valerie Olson unpacks the concept of the “system” that underlies NASA’s understanding of the functioning of human bodies and materials in extreme environments like outer space. Stacy Zabusky writes of the complicated international and interpersonal relations that make the running of the European Space Agency possible. David Valentine undertook long term ethnographic research with “technocapitalists” involved in the NewSpace industry to find out how they imagine space exploration as part of humanity’s future. And more recently, participants in a collaborative project being undertaken in the anthropology department of the University College of London are currently studying life on the International Space Station, “arguably the oldest extra-terrestrial society in low earth orbit.” Other works deal with the ways in which local communities have been transformed—for better and for worse—by the use of satellite technologies such as GPS. The work of Claudio Aporta and Eric Higgs on Inuit hunting practices comes to mind.

Through the ethnographic study of science and scientists, other anthropologists have considered profound questions about humanity’s place in the universe. Steven J. Dick writes about the possibilities of interspecies communication and the nature of intelligence in his study of the program SETI (The Search for Intelligent Life in the Universe), and Stefan Helmreich ponders the essence of life itself in his work with astrobiologists in the extreme places of the Earth.

POWER

The analysis of the effects of political and economic structures on outer space discourse and practices is one way in which anthropology can best contribute to the study of outer space. Taylor Genovese has looked at labor relations in the space industry in order to highlight the fact that astronauts are salaried state workers (usually), and not just the embodiment of heroism and nationalist aspirations.

Among the (too few) anthropological studies of the negative impacts that the development of the space industry has had on local communities outside its historical centers are studies by Peter Redfield in French Guiana, an important launch site for the French and European Space Agencies, and Sean T. Mitchell in Alcântara, location of Brazil’s aerospace base. And recent studies, such as that of Hi’llei Julia Hobart, examines the ways in which native Hawaiians have resisted the installation of the Thirty Meter Telescope on Mauna Kea.

ALTERNATIVE FUTURES

“Pity the Indians and the buffalo of outer space,” one of Jane Young’s Navaho interlocutors told her, referencing his people’s collective memory of imperialism and genocide. And indeed, drawing attention to the ways in which the discourse of space exploration tends to replicate colonialist notions of conquest, domination and extraction is one of the major contributions of the anthropology of outer space.

Another is showing how space as “the final frontier” is only one vision among many possible future imaginaries. William Lempert, for example, writes of the diversity of works of indigenous futurism which offer radical alternatives to hegemonic narratives of space colonization, while Michael Oman-Regan argues for “the queering of outer space,” as a corrective to normative images of white, European, male and heterosexual bodies in space. Of vital importance here is the insistence that the fact of human cultural diversity and the wide range of human positions and perspectives means that there is more than one possible future, even in the face of what seems to be the potentially apocalyptic context of late capitalism, marked by ecological disaster and profound inequality. The stakes are too high to limit the visions and voices allowed to matter.

ANTHROPOLOGY NEEDS OUTER SPACE

Anthropology brings to the table a history of examining themes that are highly relevant to the study of outer space: the play between identity and otherness, the value of diversity, the relation between structure and agency, and the importance of the dialogic encounter. But just as outer space needs anthropologists, the reverse is also true. Looking up from the Earth, letting ourselves be swayed not only by centripetal care, but also by centrifugal curiosity, allows for a scalar reimagining, a combination of the really big and the really small, pasts and futures, the sublime and the mundane.

The study of outer space also forces anthropologists to collaborate in new ways, working not only with “informants” (to use the old parlance), but interlocutors from a wide variety of disciplines, with a wide variety of points of view, including scientists, engineers, politicians, planners, artists, architects, communicators, theologians, lawyers, and many others, who bring their own knowledge, experiences and opinions.

These new forms of dialogue and collaboration represent a turning towards a truly cosmopolitical consciousness, an attention to the more-than-human, that, without being anthropocentric, does not imply a turning away from the human or the particular, but rather an encompassing. This play between “up there” and “down here” discovers the “multi” hidden behind the notion of a “uni” verse, at the same time as it points to what Debbora Battaglia calls a “cosmic commons,” which requires “cosmic diplomacy.” Anthropology brings ethnography, dialogue and perspective, while outer space calls for speculation, imagination and a rethinking of scales and stakes.